Last updated January 12, 2026

Johannes Vermeer's "Girl with a Pearl Earring" travelling from Netherlands to Japan – Story at Art News MSN

Exhibit with limited days left:

Brussels – BOZAR — formally the Centre for Fine Arts — "Goya and Spanish Realism" (Oct 8, 2025 – Jan 11, 2026)

A major EUROPALIA exhibition putting Goya’s work in dialogue with Spanish realism across later generations. BOZAR Website

This unique exhibition brings the groundbreaking oeuvre of Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746−1828) into dialogue with work by contemporaries and artists from later generations. With his fierce, gripping depictions of injustice, abuses and horrors of his time, Goya was the pivot in the development of a modernity firmly anchored in the Spanish realist tradition. Seventy artists — from the 18th century to the present — confront Goya’s expressive complexity and prove how his formal, conceptual and ideological legacy continues to intrigue, move and inspire..."

This 1848 painting has uncanny insight into American conspiracy thinking – Can a country born in conspiracy theories find the fine line between suspicion and paranoia? – Washington Post

In “Politics in an Oyster House,” owned by the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, the younger of two men sitting in a shabby restaurant is hectoring his elder with obnoxious vehemence. We don’t know what they are talking about, but based on body language we can make a guess: The loudmouth fellow in a rumpled hat, holding a newspaper and gesticulating aggressively, is expounding a theory of the world, tedious and detailed, based on a wild mix of reasonable and unfounded assumptions gleaned from haphazard reading, rumor and dubious research. He is, perhaps, in the grips of conspiracy thinking, a special feature of American politics at least since the Rev. Samuel Parris found the devil lurking in the shadows of Salem, precipitating the witch trials that led to the deaths of at least 20 innocent people. (Woodville later suggested that the young man was a communist.)..."

The statement prompts the question "...a country born in conspiracy theories ..." implies a basis that can be modified. Are the differences in generations and how they adapt to "conspiracy theories" such that, in this kind of thinking (which itself seems like a conspiracy theory) do the generations generate new conspiracies to accompany or dispute the old ones?

Seven-minute daylight heist at Louvre takes Napoleonic jewelry – Washington Post

It took the robbers just seven minutes to execute their daytime heist, French Interior Minister Laurent Nuñez said. They used a grinder to cut through display cases, helping themselves to precious jewelry before making their escape on motorbikes."

Break-in at Louvre in daylight burglary – UK The Times

A gang is believed to have used an extendable ladder to reach the first floor of the world’s most visited museum, then used a chainsaw to open a window and the cabinet containing the jewels."

Vandals attack painting in Madrid– MSN New York Post – October 14, 2025

Activist group called "Vegetarian Future" threw paint onto a Christopher Columbus painting at the Museo Naval in Madrid, Spain.

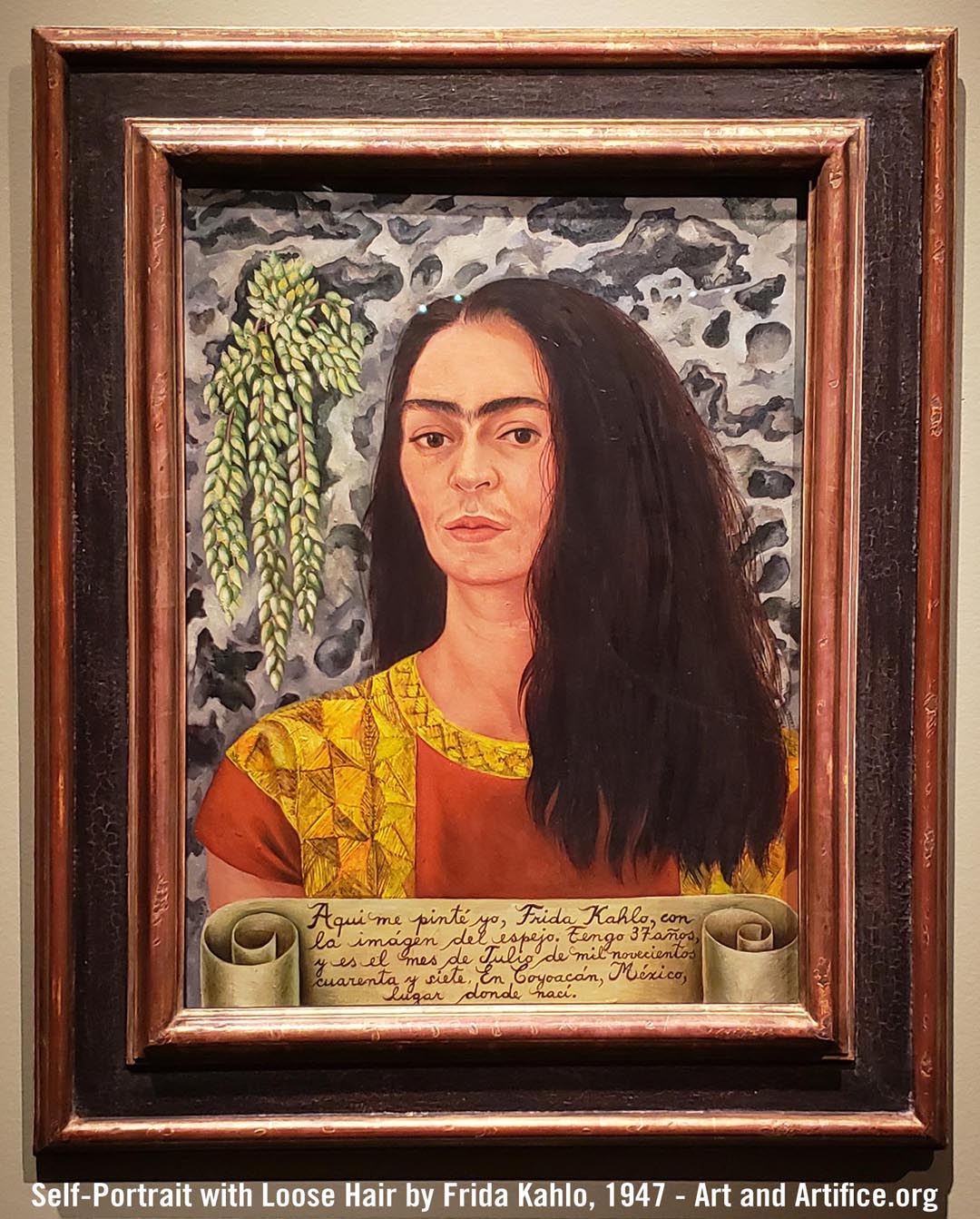

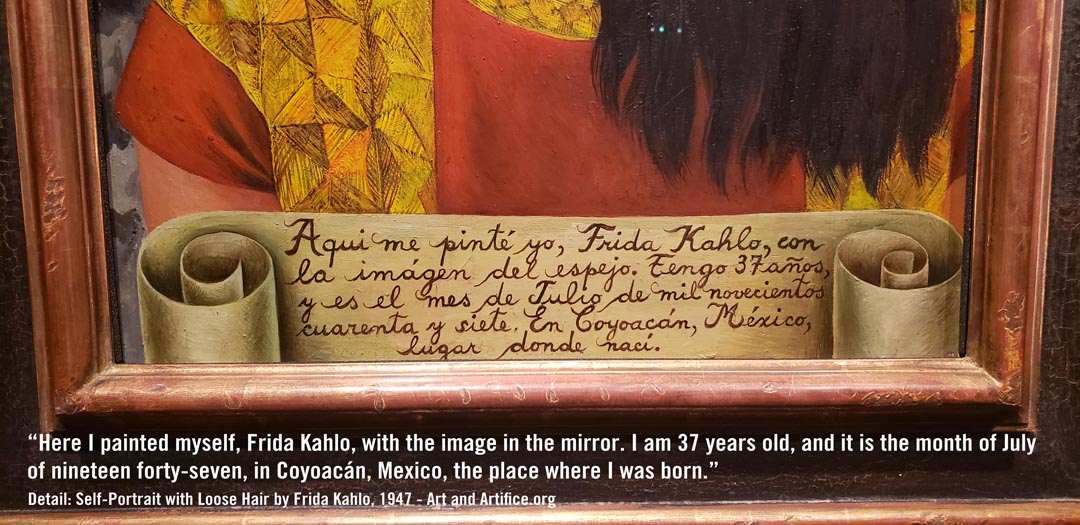

Frida Kahlo at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

I went to the Frida Kahlo exhibit with less enthusiasm and more a sense of obligation, intending to view, in person, some of the works of one of the most celebrated artists of the 20th century. In fine arts, Kahlo is completely unavoidable, in some portion because her fame has been buoyed upward through a general link to the societal effort to emphasize women artists in a sphere of culture that has been traditionally over many, many centuries, dominated by male painters.

More about the Frida Kahlo - Beyond the Myth exhibit

"Actress Salma Hayek remembered artist Frida Kahlo on the 100" – Times of India - October 2025

Frida Kahlo's "Home away from home" where her childhood collections and some artworks are shown to the public at the newly opened Casa Kahlo Museum – Morning Call - October 2025

"Mrs Job Mathew Rathes and Her Daughters" by Sir Thomas Lawrence 1804 - click image to enlarge

"Brutalist interiors" - touring the world and viewing this phenomenon of design with it's most famous expressions – Wallpaper

Ellie Stathaki discusses Faculty of Philosophy building in Novi Sad, Serbia; the Housden House in London; the Johannes XXIII Church in Cologne, Germany; and several more, all with photos.

Police in Italy search for couple that sat on museum artwork ....and crushed it – The Local Italy

"Palazzo Maffei described it as "every museum's nightmare" and told AFP on Monday it had made a complaint to the police..."

Framed Portrait of Pocahontas by Richard Norris Brooke begun 1889, completed 1907.

The controversy of authorship around the famous Vietnam War era photo "Napalm Girl" photo – le Monde – May 22, 2025

More art pages in the Archives